|

History of Route 662,400 miles from Chicago to Santa Monica

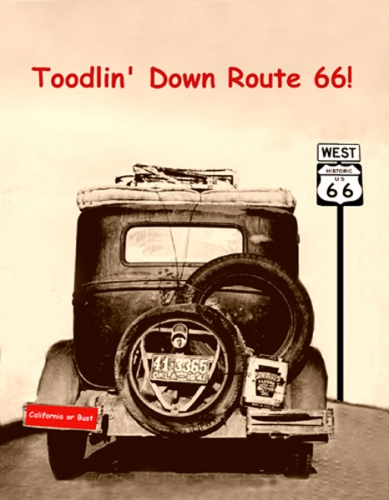

Route 66, U.S. Highway 66, Historic Route 66, The Main Street of America, The Mother Road, Will Rogers Highway, The Great Diagonal Way, Road of Flight, National Old Trails Road: From the shores of Lake Michigan in Chicago, across the agricultural fields of Illinois, over the rolling hills of the Missouri Ozarks, past the coal mining camps of Kansas, across Oklahoma--where the woodlands meet the open plains, through the ranch land of the Texas Panhandle, the mesas of New Mexico and Arizona, to the Mojave Desert of Arizona and California, and finally ending at the shores of the Pacific in Santa Monica. The drive takes you back to a bygone era, while also showing you the magnificence of the varied landscapes of America. Route 66 holds a special place in the American consciousness. It brings forth images of a simpler time, mom-and-pop businesses, a culture of Americans working hard to achieve their goals and make a difference; and icons of a mobile nation on the open road. Travelers today can easily take this journey--85% of the original alignment of the old road is still drivable--and they can experience the past in its authentic glory. Many of the original motels, diners and cafes, unique roadside attractions, filling stations, neon signs, murals, trading posts, displays of geological phenomena, and parks endure along the thoroughfare. Ghost towns, rusted relics, abandoned buildings, and remnants of places that once thrived with life and activity, are more somber testaments to Route 66’s rich past. A road trip on Route 66 has often been described as adventurous, but the real adventure resides in its unpredictability. You find yourself wondering about its beginnings and how it got to where it is today. You are anxious to know what will greet you around the next bend, and what you will learn from people you meet who live and work on the old road, as well as from fellow travelers. On Route 66, you’ll experience a heartwarming sense of being part of a big family. There is something magical about it; and it can be life-changing. Route 66 started out as a grassroots project. After devising a plan for a national highway system in 1925, various local groups in the U.S. began to build roads. It was 1940 before paved roads linked the east and west coasts with U.S. 66 being one of the major highways of that system. Route 66 had its official beginning in 1926 when the Bureau of Public Roads launched the nation’s first federal highway system. Like other highways in the matrix, the route was a cobbling together of existing local, state, and national roads. Where roads did not exist between towns, short new ones were built in order to complete a “ribbon” of roads across America. Route 66 became the first major trans-continental highway across America. The highway quickly became a popular thoroughfare, thanks to the active promotion of the U.S. 66 Highway Association, advertising it as the “shortest, best, and most scenic route from Chicago through St. Louis to Los Angeles.” Entrepreneurs Cyrus Avery of Tulsa, Oklahoma (known as the Father of Route 66) and John Woodruff, of Springfield, Missouri, deserve most of the credit for promoting the idea of an interregional link between Chicago and LA. However, their lobbying efforts were not successful until their dreams merged with the national program of highway and road development. The road received the numerical designation of “66” in 1926 and was later dubbed a “super-highway” as one of the nation’s principal east-west arteries. But it would take 12 years before the new highway was completely paved. Road work was temporarily halted when The Great Depression hit. But in 1933, thousands of unemployed men were put back to work paving the final stretches of the road up until 1938. Cyrus Avery nicknamed Route 66 “The Main Street of America.” The origin of this name came from the fact that Route 66 was “Main Street” in most of the towns it passed through. It was the preferred transcontinental route, offering better weather for traveling or vacationing than other east-west roadways. The diagonal route across the country enabled rural communities to link with big cities. Farmers in Illinois, Missouri, and Kansas were able to easily transport grain and produce for redistribution to Chicago and St. Louis. By 1930, trucking rivaled the railroad for preeminence in the American shipping industry. The Mother Road appealed to truckers who preferred driving the flatter prairie lands, with more temperate weather, over the often cold northern highways. Merchants in towns along the highway looked to Route 66 as an opportunity for attracting new revenue to their rural and isolated communities. As the highway became busier, the roadbed received improvements and support for infrastructure businesses, especially those offering fuel, lodging, and other travel amenities. Even though The Great Depression cast its devastating blow to the nation, it produced an ironic positive effect along Route 66. For eight years, from 1931 to 1939, dust storms blew across the southern plains. Then came in a yellowish-brown haze from the south and rolling walls of black from the north. The simplest acts of life--breathing, eating a meal, taking a walk--were no longer easy. Children wore dust masks to and from school. Women hung wet sheets over windows in a futile attempt to stop the dirt from entering their homes. And farmers watched helplessly as their topsoil blew away, resulting in failed crops. The agricultural devastation contributed to lengthening The Depression, and the effects were felt worldwide. The movement of people on the Plains was also profound. The Mississippi basin became known as the Dust Bowl. Hundreds of thousands of farmers, in economic ruin, abandoned their homes. They loaded their meager belongings in their cars and pickup trucks and headed west, hopeful for a better life and employment. Many towns along Route 66 created camping areas or motorist camps where the poor, homeless travelers could sleep in their vehicles for free. For them, Route 66 was the road to the “promised land” of California, where endless sunshine, bountiful fruit, nut and vegetable harvests, and paying jobs were waiting for them. This mass migration of destitute people fleeing their homes increased traffic along the highway, providing commercial opportunities to a multitude of businesses. In the fall of 1939 the rain came, finally bringing an end to the drought. During the next few years, the country was experiencing prosperity, and the plains once again became golden with wheat. World War ll caused a market decline in tourist traffic, but new business was stimulated along U.S. 66 when it acted as a military transport corridor, moving troops and supplies from one military garrison to another. Motels saw an increase in occupancy when families of servicemen stationed at military bases stayed for long stretches. But more significantly, Route 66 facilitated perhaps the single greatest wartime mobilization; job seekers headed for California, Oregon, and Washington to work in defense plants. When the War ended, traffic increased with rationing and travel restrictions lifted. Auto ownership grew dramatically over the next ten years, with 52.1 million cars registered in 1955 (compared to the 25.8 at the end of the War). With more already established leisure time, families headed west on Route 66 to the Grand Canyon, Disneyland, and the beaches of Southern California. With heavier traffic, businesses along the highway boomed and the perception of Route 66 as a Dust Bowl migration route changed to one of freedom and kicks. The bleak images of John Steinbeck’s 1939 classic novel, The Grapes of Wrath, and the subsequent 1940 movie re-creation were replaced by the upbeat lyrics of Bobby Troup’s song, Get Your Kicks on Route 66, first recorded by Nat King Cole in 1946. Bobby was the former drummer with the Tommy Dorsey Band and a Marine Captain in the War. The 1950s proved to be a glorious era for Route 66 travel. Windows were rolled down, radios were blaring the new Rock ‘n’ Roll hits, and Americans had put their worries behind them, taking to the freedom of the open road. The promise of a better life loomed westward...and businesses along the Route flourished. The concept of fast food came into being, and spawned the American craze of hamburger stands, home-style cafes, roadside diners, and malt shops. Curio shops and attractions like rattlesnake ranches provided welcome breaks from driving. Motor courts (or motels) came into existence, and service stations competed for business boasting “friendly attendants” plus “registered restrooms”. In the early 1960s, the TV series Route 66 documented the adventures of two young men “seeking their kicks” in their shiny new Corvette. Even though only a few episodes of this program were actually filmed on Route 66 during the four years the show was on television (1960-1964), it did a lot to immortalize the Mother Road. It enabled viewers to be part of the freedom of traveling roads throughout America. Just as enormous traffic in the decade after World War ll sent Route 66 into a boom time, over established overcrowding of the highway eventually signaled its demise. President Eisenhower, who had witnessed the military advantages of the German Autobahn during WWll, supported the passage of a law to construct a new system of high-speed, limited access, four-lane highways--today’s interstates. Five new interstates, I-55 (Chicago to Salt Lake City), l-44 (Salt Lake City to Oklahoma City), l-40 (Oklahoma City to Barstow, California), and I-15 (San Bernardino to Santa Monica) drew traffic away from Route 66 over the next three decades. Interstate construction coincided with economic consolidation as evidenced by the growth of branded gasoline stations, motels, and restaurant chains. The 1984 bypassing of the last section of U.S. 66 by I-40 in Williams, Arizona led to the official decommissioning of the highway in 1985, impacting countless businesses and communities along the route. It was a devastating blow, but in true Route 66 fashion, members of public and private organizations and governmental agencies who understood the highway’s historical and social significance, started campaigns to preserve and commemorate the road. Part of Route 66 received new designations, as state and/or National Scenic Byways. Tourists again came to the old road, and businesses saw another era of visitors wanting to experience history and the actual drive on all of America’s Main Street. The wonder of this historic road has been documented in numerous guide books. One of the best known is Road 66: The Mother Road, by a leading Route 66 proponent, Michael Wallis. It was depicted in the 2006 animated Pixar film, Cars, by producer/director John Lasseter. The movie brought awareness of Route 66 to a whole new generation. For all the values it represents...and all the images it embodies, generations of both Americans and international visitors have a fondness, perhaps even a passion, for Route 66. The Mother Road’s existence is pure Americana, a reminder of the strife and hardships of its inhabitants and travelers of the past. It enables visitors from across the globe to understand and appreciate its significance and long history. Consider Route 66 as a future road trip for you and your family. Whether you take the drive in full or in part, you’ll truly discover that the joy of traveling is not so much in the destination, but the journey itself. © Copyright 2018 Preserve America |